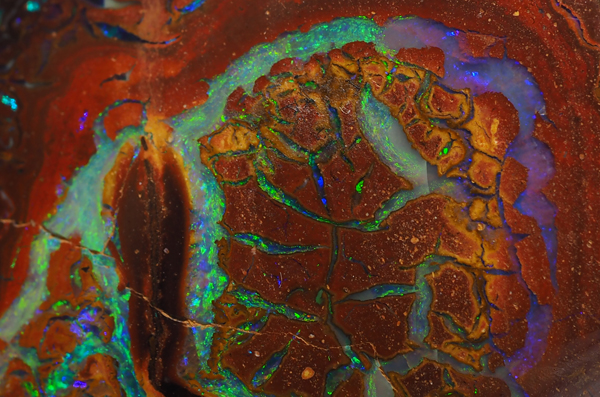

Earth magic: the message within the opal

Lately I’ve been immersed in the extraordinary beauty of opals.

No other stone can deliver quite the character that opals can.

Don’t get me wrong – I love many gemstones, but I believe that when we’re drawn to something (and particularly if it gets a little bit unbalanced and obsessive!), this indicates there is energy or information here that we need to pay attention to.

I’ve got quiet opals with dark faces but when they catch the light at certain angles there’s a flash of brilliant green as pure as the green ray of the heart chakra.

Others are steadfast earthy rocks (brown as the earth they’ve come from) with marvelous glowing cores like multicoloured lava. And others have a quiet purity of intention, a preternatural glow of meltingly luminous greens, reds and blues.

When I first heard the description of white opal as the ‘Seed of the Holy Fire’ this felt so pure and true. Beneath the haze of white light there are dazzling flashes of inspiration that evoke for me the Ecstasy of St Teresa, burning with mystical Eros, as captured so beautifully in Bernini’s extraordinary sculpture.

No stone offers quite the spectrum of colour play – or, in fact, the extremes of price – as does the opal.

Thus, there is something wonderfully egalitarian about this stone. And in particular the Boulder Opal, which contains all the colours of its fancier cousins the White and Black Opals. It’s simply that its veins of colour are usually more narrow. Once they used to be sliced down and glued onto slabs to produce little ‘triplets’ and ‘doublets’ that appeared in ubiquitous, uninteresting jewellery in every tourist trap across Australia.

Now we celebrate them in their natural state, their colours still contained in the matrix of rock that enabled their growth.

Opals are actually water turned to stone. You can literally see the liquid flows in the patterns of many opals, telling the story of how water and minerals trickled into channels and spaces in rocks, or were laid down in dissolving wood and the bones of ancient animals. And then transformed, over unimaginable years, into these glorious combinations of earth and light.

Unlike other gems such as diamonds or rubies or amethysts, they don’t grow deep underground in volcanic pipes, or fiery larval flows, or dark caverns.

Opals began in the sands of a vast inland sea that covered the heart of the continent 100 million years ago.

I source my opals directly from the miners in my home town of Winton (in ‘outback’ Queensland), which is on the edge of this ancient sea, and most recently has been made famous for its dinosaur fossil discoveries. In fact the mines are about 120kms south of the town and are still mined by individuals (very clear traceability to source here!). Here there are none of the giant mining pits or multinational conglomerates associated with diamond mining.

Opal is not, strictly speaking, a crystal, but an amorphous ‘mineraloid’ of hydrous silicon oxide.

Unlike other stones it does not occur as crystals but as small veins, globules and crusts, usually condensed from silica-rich solutions. It can also replace the skeletons of many marine organisms and plants, which is how you get opalised shell and wood – fossils that have become jewels!

It owes its fragility to the loss of water when it is exposed to air. The surface becomes crazed with tiny conchoidal fractures. The characteristic play of colours in many opals result from the way that light is dispersed according to the angle of incidence (the angle in which the light strikes the surface).

Opals haven’t been so popular in Australia – most is sold into the US market.

I believe this is largely due not only to our ‘cultural cringe’ but also to the design abuses the stones suffered in the 70’s and 80’s!

And the increase in their popularity now is part of the rising interest in preserving our natural world. The fragility of opals is an echo of the fragile balance within Australia’s eco-systems.

In a time that feels like we are on the verge of an ecological crisis, the opal is a quiet reminder of earth magic.

In an era when everyone is trying to escape into the virtual worlds of technology – and the belief that science will solve our ecological problems – the opal evokes the sublime beauty of the material world.

This sensation of awe and delight is not only good for us, it reminds us of the preciousness of this land in which we live. The opal plays its role in re-orienting us around respect and love for the world of matter.

And this simple re-orientation is perhaps the singularly most important shift we can make to solve what ails us in modern times.